After a one-year delay due to the pandemic, the Summer Olympics are here! While things will not be exactly the same due to lingering health safety concerns, one thing will remain – national pride. Spectators around the globe will tune in to cheer on their country hoping to hear their national anthem and see their athletes take the top spot on the podium. Close your eyes and you can hear the celebratory chant, “U-S-A! U-S-A! U-S-A!”.

While a gold medal is every Olympic athlete’s goal, there is no shame in taking home silver hardware. Also, spectators often find themselves pulling for an international underdog or a foreign athlete with an inspiring story. In short, it is okay if the U.S. is not on top every time. The same is true in the investment world.

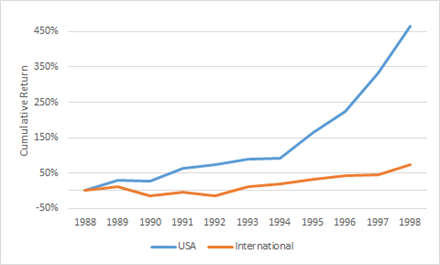

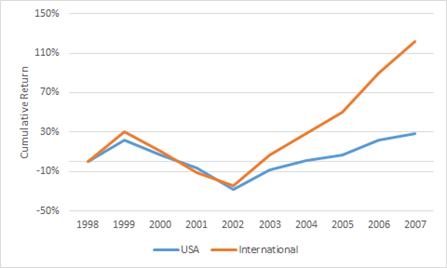

Consider the situation where the United States has bested the rest of the globe for eight of the past ten years. America’s dominance fuels optimism of additional success. Why would anyone bet against the U.S.? This describes 2021; but, global investors found themselves in that exact position at the beginning of 1999. The United States had prevailed in 80% of the prior ten years. The MSCI United States index had posted an 18.9% annualized return. The MSCI World ex USA index, by comparison, delivered only 5.6%. Who needed the other countries? U.S. investors.

Over the next nine years, the U.S. would outpace foreign shares only two times. The MSCI All Country World ex USA index generated 9.2% on average per year versus 2.8% for the MSCI United States index.

The debate is bigger than domestic versus international, though. This is because the geographic allocation decision is not mutually exclusive. It is not a matter of USA or the rest of the world. In Olympic parlance, it’s not “gold or bust”. A globally allocated (U.S. and foreign) portfolio would have been more diversified than one holding all American or all international names. When U.S. shares dominated 1989-1998, a global portfolio would have returned 10.7%; and, when shares abroad were on top from 1999-2007, an all-world allocation would have provided 6.0%. In both cases, the global portfolio trailed the leader but outpaced the laggard. This is how diversification works.

It would be wonderful to know in advance which area will outperform and load up on exposure. Of course, we cannot predict, so a focused bet could also go awry. Spreading the allocation around acknowledges two things: (1) some assets will perform better than others and (2) it is impossible to know which ones. The prudent steps to take in this scenario, respectively, are to have exposure to all assets and not allocate too much to any single asset.

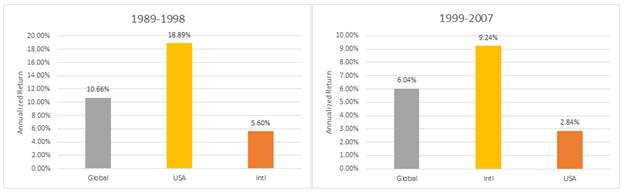

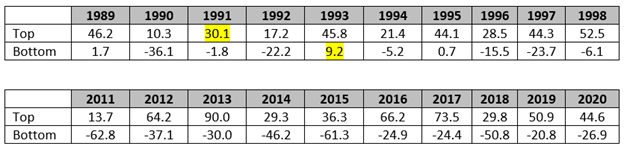

Looking at country level data, an interesting dynamic can be observed. During the U.S.’s strong 1989-1998 performance, it was the top performing country only once in 1991. (It also came in last in 1993.) Similarly, from 2011-2020, another period where international lagged, American shares were on top… zero times. The best placement achieved during that period was fifth in 2011. The upshot is that there is usually a better performing market outside the United States. Having broad international exposure ensures that this return is captured.

Another takeaway from the above tables is the range of returns. The returns generated by other countries are both widely varied and independent from those produced by the U.S. Again, this is a sign of diversification working. It is desirable to have a portfolio of assets that do not move in lockstep. Having all the components move up together at the same time sounds great; however, the flip side would likely be true as well. Diversification forgoes the chance to be fully exposed to the top performer but also eliminates the risk of having a full weighting to the worst player.

Pulling for your country during the Olympic games is part of the experience. So, too, is the realization that you “can’t win ‘em all”. Global diversification admits that your country will not always take the gold. Having broad exposure, however, means that you will have some allocation to first place. Conversely, by not being all-in on one country, you’ll never come in last. Rather than going for the gold and risk taking home bronze, go for the silver.

As Chief Investment Officer, Dan is responsible for developing Trust Company’s investment strategy and managing client portfolios.