January 12, 2023

Bah, Humbug!

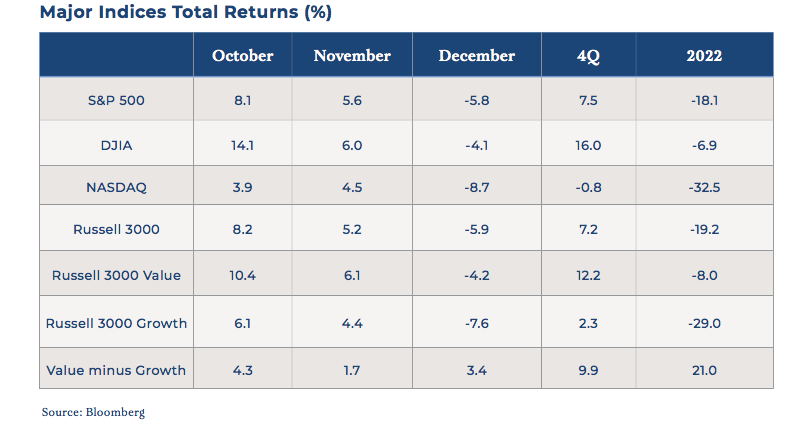

Santa delivered coal to investors during December, with all major U.S. indices finishing the year the same way they started, crashing through the snow. No Santa rally ever materialized, with the S&P 500 returning -5.8% for the month. It was a fitting end to the worst year for stocks since 2008. Spooked by rising inflation and interest rates and a slowing global economy, the S&P 500 returned -18.1% for the year. The industrial-focused Dow Jones average fared better, delivering just a 6.9% negative total return, while the tech-heavy NASDAQ plummeted 32.5% for the year.

Equity returns continued to exhibit prevailing patterns during the fourth quarter, with value continuing to outperform growth, and with old-economy equities outperforming their new economy rivals by a considerable margin. As interest rates climbed, investors demonstrated a strong preference for stocks with defensible valuations over stocks priced on future earnings potential. Some of this is just math—asset prices are supposed to reflect a series of future cash flows discounted back to the present, and when discount rates rise, asset prices decline. But some of this is not math—the reality is that markets are more than just discounting machines; in the near term, as Benjamin Graham first pointed out, markets are voting machines. As stock price appreciation lost its momentum last year, the stocks that had been market leaders began to fade. Market participants began to “vote” for other stocks, and the more the voting had driven the prices of those leadership stock prices up above intrinsic value, the further they had to fall.

The good news for little boys and girls is that the quarter itself was actually rather strong. The S&P 500 finished the quarter up 7.5% and the Dow Jones returned a full 16% while the NASDAQ was down less than a percentage point. Specifically, the good news was that inflation, while still stubbornly high, may have crested. In October, the growth of the consumer price index was below expectations, creating hope that November’s would also be cooler than anticipated, which it was. Of course, the bad news is that the benchmark interest rate range is now the highest it has been in 15 years (4.25% to 4.5%). The yield curve (the difference between short-term and long-term interest rates) is now steeply inverted, as the effects of higher interest rates filter through the economy.

Because of these two benign inflation readings (and January’s number, which also showed cooling), hope has emerged that the Fed is much closer to the end of its rate hike campaign than it is to the beginning. All else equal, that would be a positive development for markets. Unfortunately, all else is not equal. The economy is only just beginning to respond to this more restrictive monetary policy; the impact of these interest rate increases may not be fully evident for some time. It’s certainly evident in pockets. Single-family housing starts have fallen well-below long-term averages, and used-car prices, which skyrocketed during the pandemic, have fallen dramatically. With the price of money having changed so much in such a short amount of time (recall that a year ago the lower end of the Fed Funds rate was… ZERO) there’s little wonder that liquidity has receded from markets and that assets of all kinds have been dramatically re-priced. The trouble is, nobody really knows how much impact the dramatic increase in interest rates will have on the economy. If the Fed turns out to have been too heavy-handed on the brake, the economy could sputter and corporate earnings could fall more sharply than expected, probably sending the market lower. If the Fed has not done enough, then inflation could re-accelerate, eating away purchasing power and forcing the central bank to raise interest rates even higher and with less room for judicious application. That too would be a negative. The Fed really does have its work cut out. Goldilocks doesn’t come along every day.

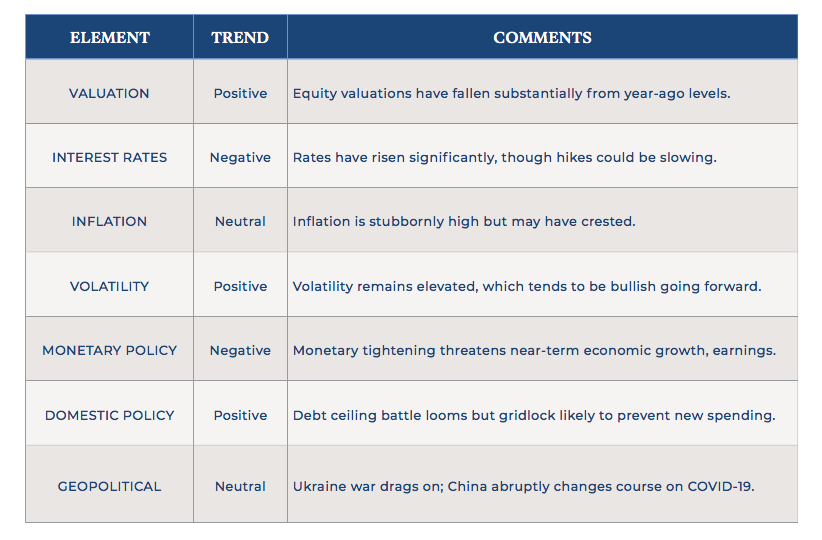

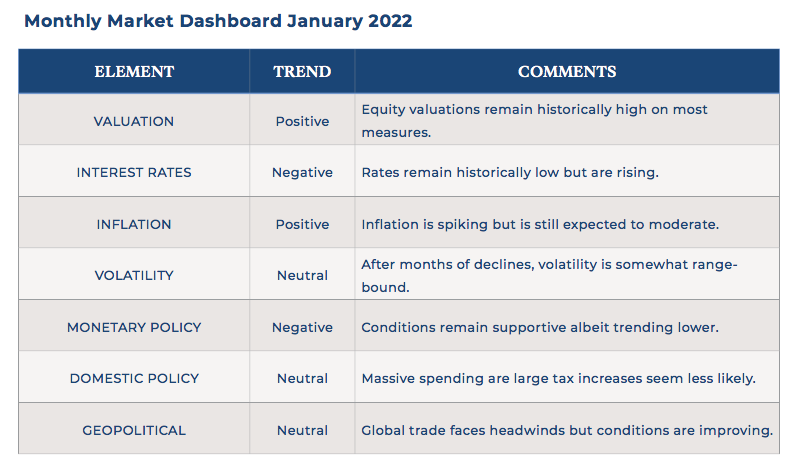

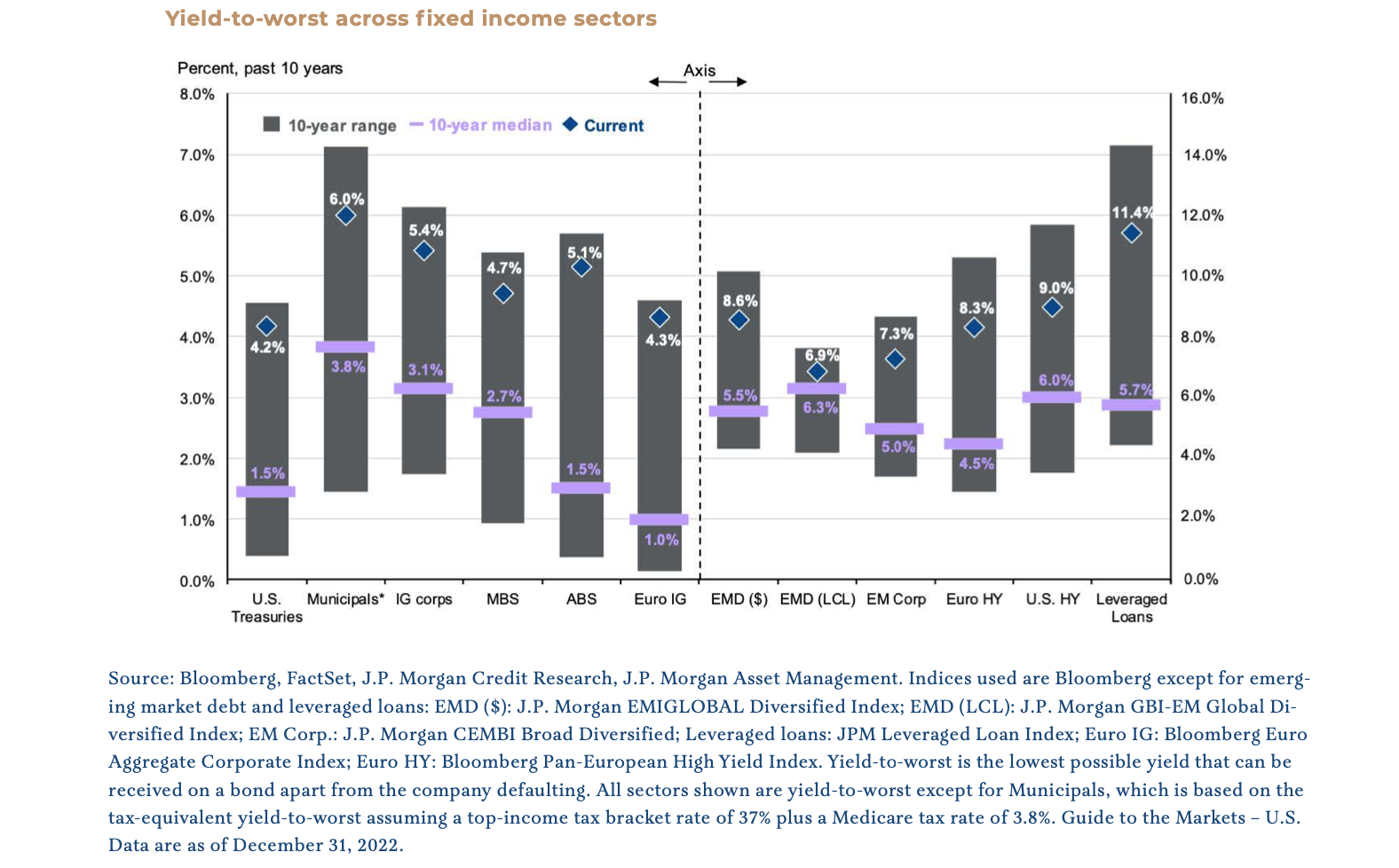

For a lesson in just how quickly markets can change (and for a dose of humility), let’s take a peek at our market dashboard chart from January 2022.

The first element turned out to have been pretty much all one needed to know; with equity valuations so high, north of 20x forward earnings, it did not take a lot of bad news or negative surprises (rate hikes and Ukraine to name a couple of examples) for the wind to get knocked out of the market. Yes, interest rates were historically low, but they did not stay historically low. Inflation was already spiking but remained elevated throughout the year, which was not the consensus expectation a year ago. Volatility had been declining but spiked significantly several times during the year. Monetary policy certainly became markedly less supportive, and the Ukraine conflict was obviously absent from anyone’s dashboard. Compared to this month’s outlook, last year’s was decidedly tougher to be bullish about. But one condition was fairly obvious; value was teed up to outperform, and it did.

The Killing Frost?

Years ago, I was interviewing John Medlin, former chairman of Wachovia Bank and North Carolina business community titan. This was in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis (and long after Medlin’s tenure at Wachovia) and I asked him about his outlook for banking and the economy. He said he was concerned that because of all the economic stimulus injected into the economy that “we never had the killing frost.” In Medlin’s mind, easy money policies merely delayed the eventuality that weaker firms would fail and that free markets would prevail. At the time, neither one of us knew we had just embarked upon what would be the longest bull market in history, one that only COVID-19 would upend, and then only with the shortest bear market in history. Using its GFC playbook, the Fed rode to the rescue again during the pandemic, dropping rates to zero, flooding the world with liquidity and boosting financial markets for the better part of another two years.

So last year was certainly a historically lousy year in financial markets. On a percentage change basis, it saw the biggest monetary tightening cycle in modern financial history. But was it Medlin’s killing frost?

It certainly felt that way for both growth investors and bond investors alike, who experienced stinging losses. Growth stocks and long-duration bonds got creamed by rising interest rates as the far-off cash flows on which valuations depend shrunk in present value terms. An equal-weighted basket of Meta, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google lost 43% last year. Tesla lost 65% of its value. Meanwhile, toward what one would ordinarily say was the other end of the risk spectrum, 60/40 portfolios also took a licking, down 16% on the year, the worst performance since 2008 and the second-worst since 1976. As interest rates took off, the volatility-dampening contribution that fixed income normally adds was overwhelmed by mark-to-market losses. All in though, outside of the former market darlings and bonds priced for perfection, experience was bad, but perhaps short of horrific. A cold snap for sure, but killing frost?

I’m not convinced we have had it yet, though my ability to predict the precise timing of future events has not improved since my conversation with Medlin. Of course, as Warren Buffett likes to say, it’s a lot easier to predict what’s going to happen than when.

Still, let’s contemplate the scenario in which the worst is behind us. There are valid reasons to believe this is the case. Two down years in a row are rare; since 1926, the S&P 500 has experienced back-to-back declines only eight times. Rarer still are annual market declines of 18 percent or more—that’s only happened seven times since 1926. Even rarer is an annual decline of more than 18% followed by another down year. The last time that happened was 1931—Herbert Hoover was president, Prohibition was ongoing and Dean Smith had just been born.

On the other hand, perhaps this time is different. Perhaps interest rates cause greater damage to the economy than anticipated, sending corporate earnings lower and financial markets too. Alternatively, maybe it turns out that the Fed has not done enough, and inflation reignites. The conventional wisdom has been that inflation will be easier to tame than in the 1970s because unions wield much less power today and fewer workers are subject to collective bargain agreements with cost-of-living wage increases. This is a white-hot labor market though, and it could be the case that employees wield considerable power as inflation drags on, causing the Fed to jack up interest rates even more. Does that sound entirely out of the question?

Of course, we just don’t know. But looking at the fact pattern, we can make a few observations.

What We Know

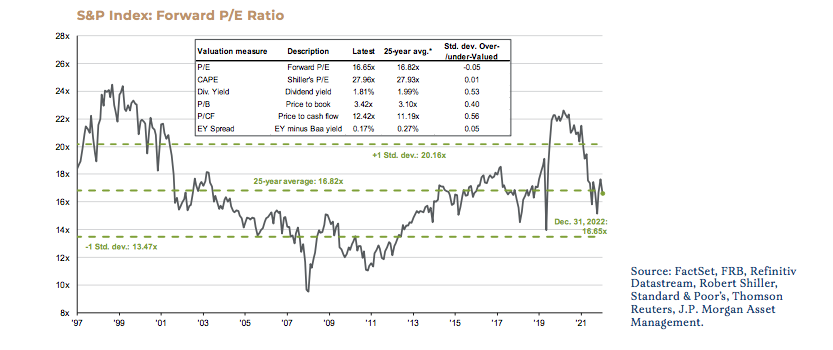

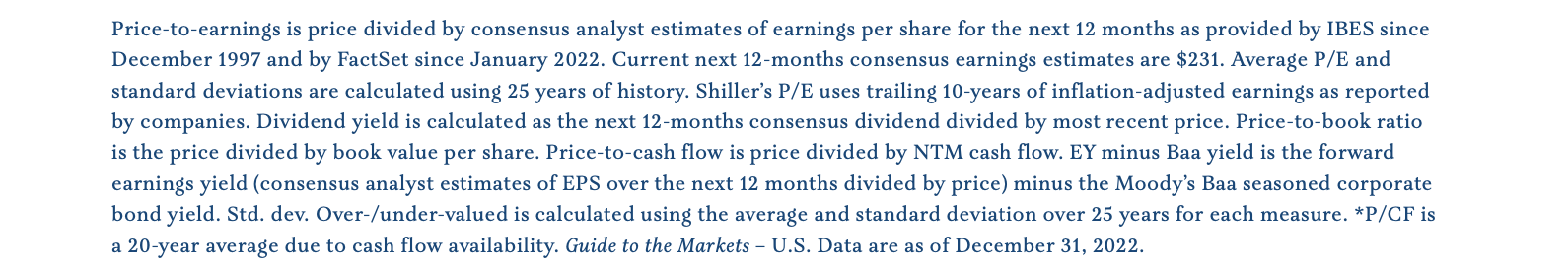

The first is this—based on history, not to mention logic, investors experience better future returns over the long-term when entry valuations are lower vs. higher. Said another way, it’s better to pay less than more. Just over a year ago, the price/earnings ratio on the S&P 500 was above 22x, more than 30 percent above the index’s 25-year average of 16.8x. Fast forward to year-end, and the index was trading at 16.7x. It doesn’t take a math major to understand that one’s odds of future success have likely improved.

While the advantage is not as evident in the short term, there is a meaningful correlation between valuation and subsequent returns even over a 5-year horizon.

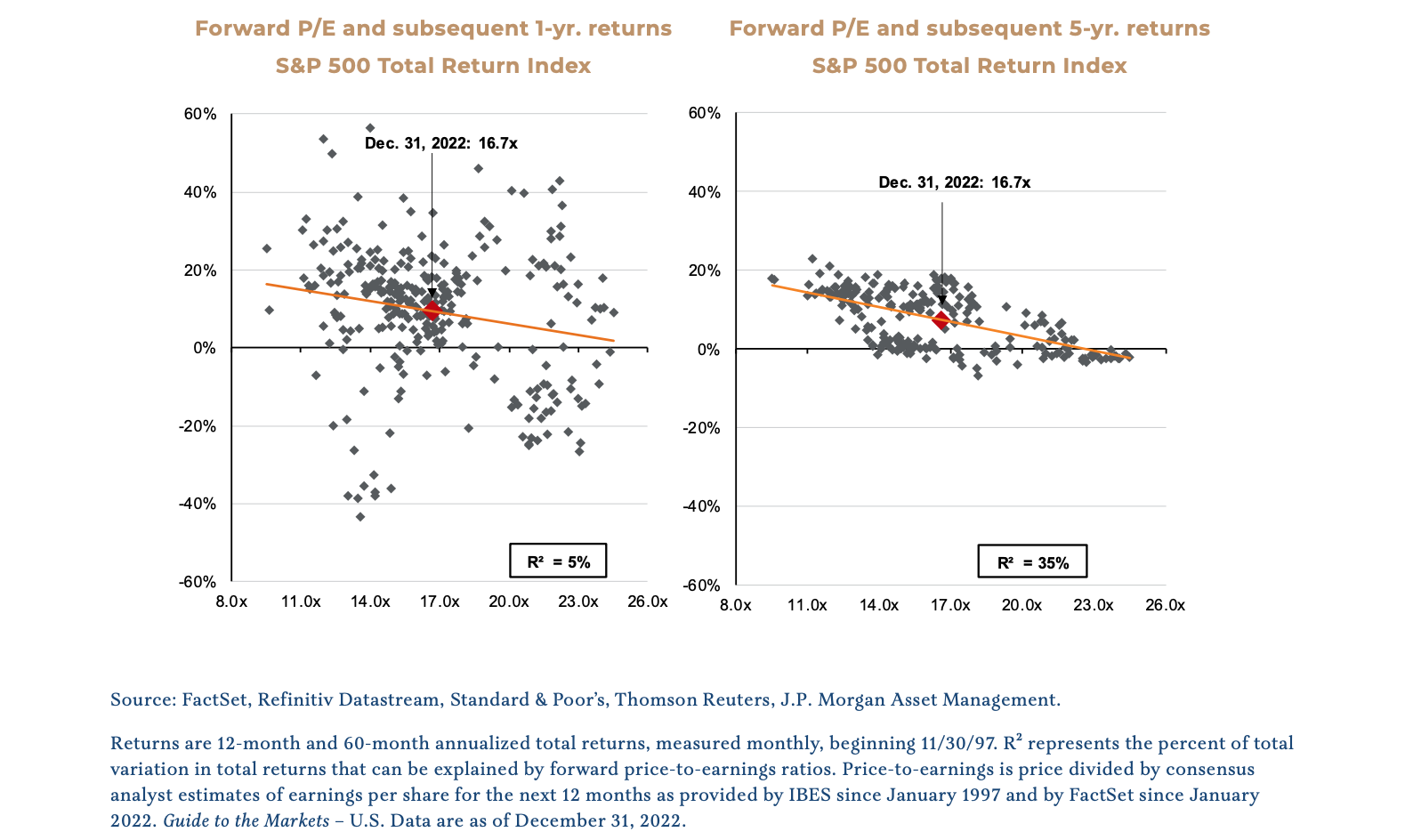

Second, by extension, we can look at various sectors of the market and make similar observations. Specifically, we would say that value is still more attractive than growth. Well, we would pretty much always make that statement merely through adherence to the logic in the previous paragraph (all else equal, better to pay less than more), but the reality is that growth stocks are still more expensive than their historical average and value stocks are still slightly cheap, and certainly more attractive than value on a relative basis, as the chart below shows.

Beyond that, it is also our observation that higher interest rates represent more competition for capital. When the risk-free rate goes from effectively zero a year ago to more than 4.2% such as it is at the time of this writing, investors need a lot more convincing that they need to reach for yield. Paltry yields on safe investments drove investors to buy riskier assets for years. That is simply no longer the case. Moreover, now that these risky assets aren’t attracting new buyers, the outlook for pricey growth stocks dims as investors bail and selling accelerates.

Buying an expensive stock is a risky game; it’s a lot like buying a stock of a company with a lot of debt—it works fine as long as there’s plenty of new cash coming in, but if there’s a hiccup, look out below.

For an extreme example, look at what’s happened in cryptocurrencies, which are not stocks even though speculators trade them on exchanges as if they are. Cryptocurrencies may or may not have a bright future, but what they do not have is intrinsic value—there’s literally no “there there.” A crypto “asset” does not represent a claim on a cash-generating business somewhere. It is, at the end of the day, a token. If nobody buys it from you, it will sit in your digital wallet earning nothing until either the power goes out or someone steals it from you. The owner is 100% dependent on “the greater fool” coming along and taking it off his or her hands. Well, for several reasons, crypto fell out of favor last year. Instead of trading like the inflation hedge crypto was touted to be (during the most inflationary period since the 1970s), it traded a lot more like a tech stock index.

To be fair, the market for crypto is brand new, so of course it is highly speculative, just like tech. It’s also complicated stuff, like a lot of tech, and I make no representation of being an expert in it. But at least in tech, or growth, I understand the game. You buy a big basket of it and a lot of it goes to zero, but you net some ginormous winners also, raising your returns to something respectable, and you also have legal ownership of these assets according to well-recognized laws in powerful countries. As the events of the last several months have shown, if somebody runs off with your crypto tokens, you get bupkis.

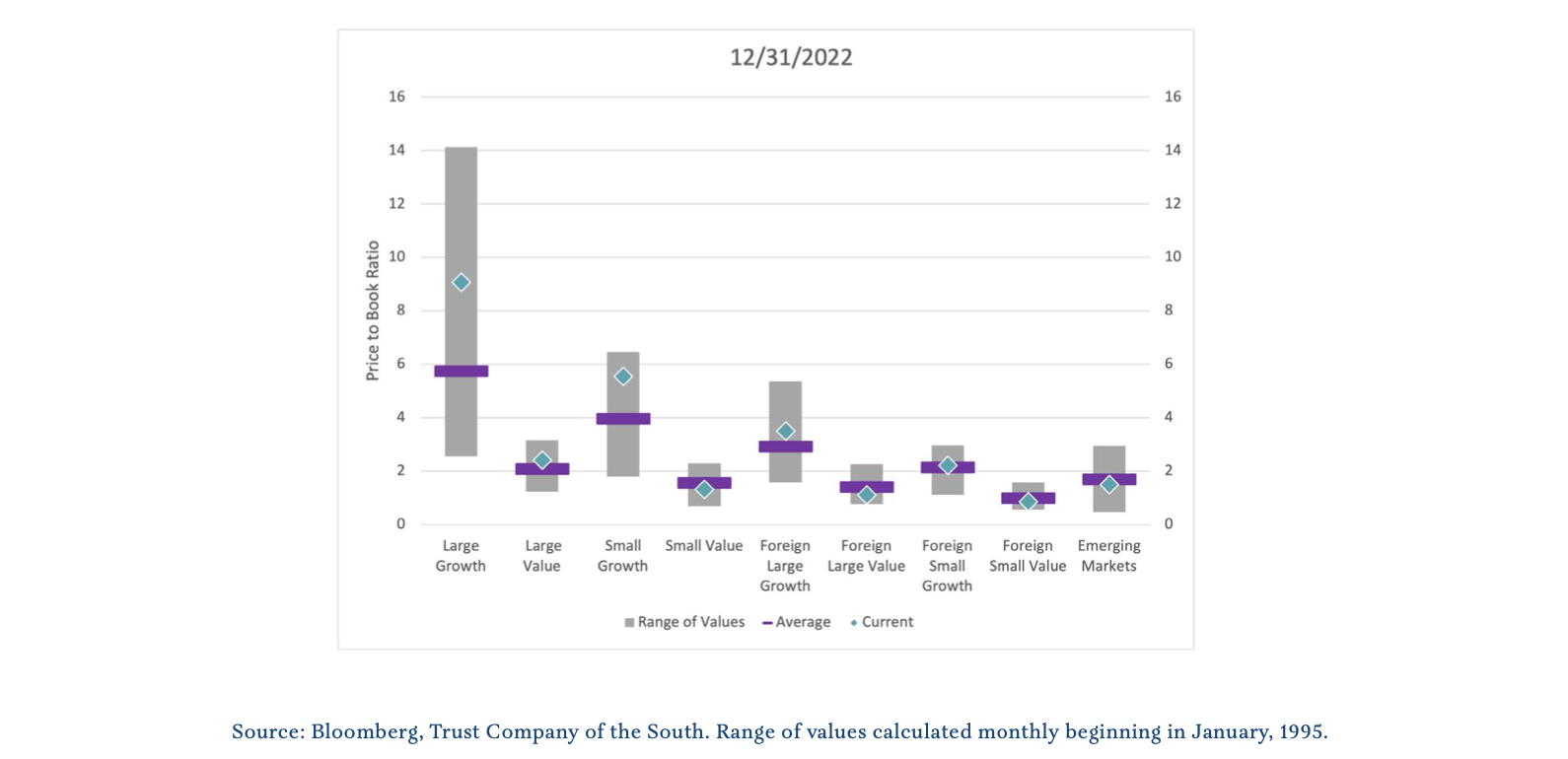

Even though higher rates wreaked havoc on bond prices too, there’s a “there there” for bonds. Bonds represent a promise to pay a stream of payments over time, and they’re often backed up by specific assets as collateral. That’s a lot different from a digital image of a dog or a bored ape. Barring default, the bondholder will collect the promised stream of payments, no matter what happens to the bond price. That’s important for bondholders to remember; they may be looking at significant mark-to-market losses in their portfolios but they’re just mark-to-market losses. In all likelihood, those losses will reverse over time and the bonds will pay at par.

For the first time in years, bond yields provide an attractive complementary return to equities.

To be clear, we do not believe investors should blow out of equities in favor of bonds, but rather consider whether bonds might have a place in a portfolio after all, given the far more favorable interest economics.

For permanent capital, equities offer by far the best long-term appreciation potential, though the ride will be lumpy. Investors should remember that over time, their biggest gains will come from the power of compounding. I recently came across a great description of how to approach long-term investing and protect the compounding effect; it was in a recent letter from Howard Marks, a great value investor. He wrote:

“I love the idea of the automated factory of the future, with its one man and one dog. The dog’s job is to keep the man from touching the machinery, and the man’s job is to feed the dog. Investors should find a way to keep their hands off their portfolios most of the time.”

Value In An Interesting World

In summary, value seems poised to outperform as higher rates bring about more competition for capital and as growth’s momentum evaporates. This is not a prediction, just an observation. It’s why we tilt toward value in the first place. If anything, we think the case for value has grown stronger. Interest rates are kind of like gravity; when they’re low, investors make great leaps of faith and take greater risks. Now that the interest rate genie is out of the bottle, it is a force that doesn’t just dissipate—it attracts savings naturally until that excess liquidity dries up, which is the whole point of what the Fed is trying to do.

This is an important point. Yes, market returns were rotten last year, but the economy was quite healthy, with real GDP growing at 3.2% as recently as the third quarter. The labor market is still smoking hot, with unemployment at 3.5%. While financial markets swooned last year, the real-world economy did not. Only late in the year did housing begin to meaningfully decelerate, and a smattering of tech layoffs begin to appear in the headlines. The Fed’s goal is not to cause financial market pain—it is to cause just enough real-world pain to smother inflation. Not until this has occurred will financial conditions be deemed sufficiently tight.

Is the planned economic bloodletting already discounted into markets? Markets are highly efficient over the long term but less so over the short term, so it’s hard to say. On the other hand, for eight of the last nine recessions, the S&P 500 did not bottom until the recession was underway (and for the other one, in 2001, it did not bottom until after it was over).

The Fed-engineered inverted yield curve does not guarantee we will have a recession in 2023 but it certainly suggests deceleration. In such an environment, we believe investor sentiment could deteriorate, dampening valuations, and sentiment might be expected to deteriorate the most in areas in which valuations are particularly high.

Remember that bear markets do not destroy value—they merely reveal value destruction. Bear markets—when animal spirits flag—are when past misallocations (e.g. GameStop, AMC, Dogecoin, FTX) reveal themselves.

Interest rates fell consistently for 40 years, creating hugely favorable conditions for markets, and, in particular, produced a bonanza for the leveraged. Partly as a result, we never saw John Medlin’s frost. Will this year yield some chilly surprises for some folks? It will be interesting to see.

For more information, please reach out to:

Burke Koonce III

Investment Strategist

bkoonce@trustcompanyofthesouth.com

Daniel L. Tolomay, CFA

Chief Investment Officer

dtolomay@trustcompanyofthesouth.com

Click here to download the PDF.

Disclosures

This communication is for informational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose, as it does not constitute a recommendation or solicitation of the purchase or sale of any security or of any investment services. Some information referenced in this memo is generated by independent, third parties that are believed but not guaranteed to be reliable. Opinions expressed herein are subject to change without notice. These materials are not intended to be tax or legal advice, and readers are encouraged to consult with their own legal, tax, and investment advisors before implementing any financial strategy.