With US stocks outperforming non-US stocks in recent years, some investors have again turned their attention towards the role that global diversification plays in their portfolios.

INTRODUCTION

For the five-year period ending March 31, 2019, the S&P 500 Index had an annualized return of 10.91% while the MSCI World ex USA Index returned 2.20%, and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index returned 3.68%. As US stocks have outperformed international and emerging markets stocks over the last several years, some investors might be reconsidering the benefits of investing outside the US. While there are many reasons why a US-based investor may prefer a degree of home bias in their equity allocation, using return differences over a relatively short period as the sole input into this decision may result in missing opportunities that global markets offer.

Although international and emerging markets stocks have delivered disappointing returns relative to the US over the last five years, we will show that historical data support global diversification and that the human brain may be playing tricks on domestic investors all over the world.

THERE’S A WORLD OF OPPORTUNITY IN EQUITIES

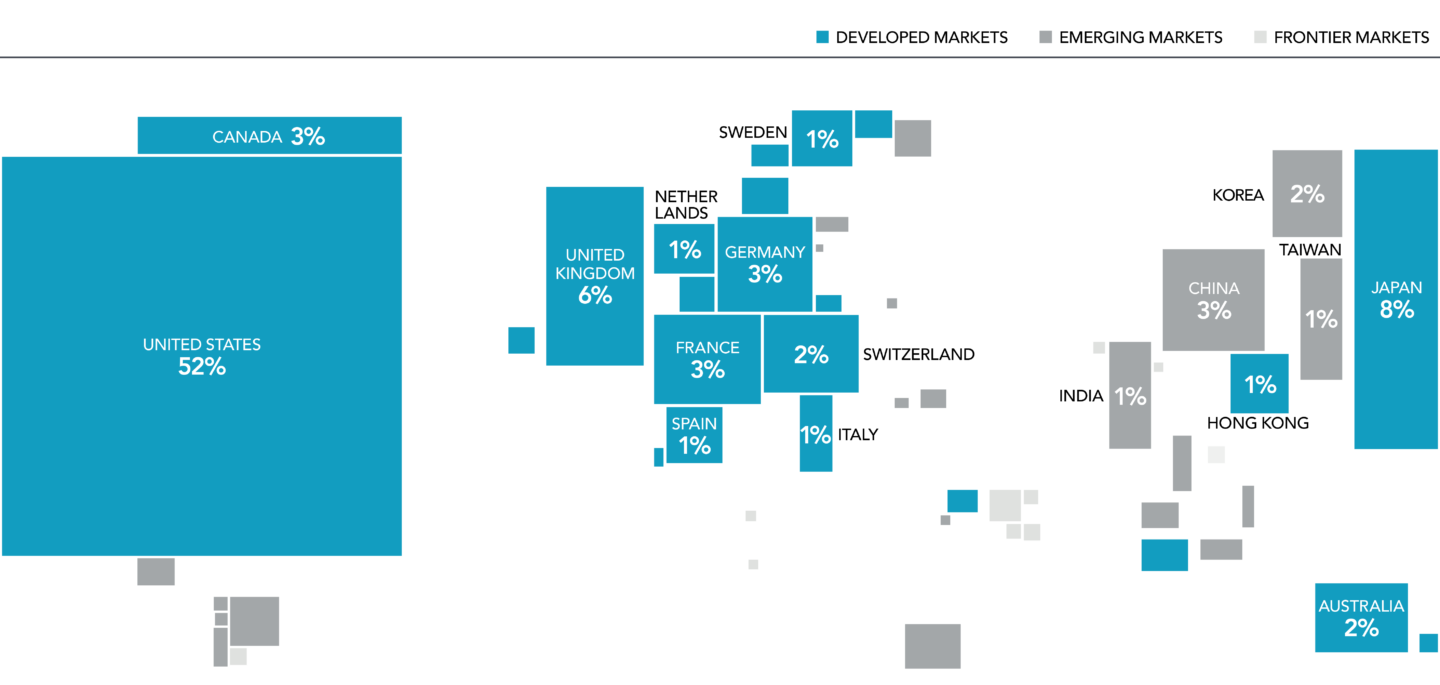

The global equity market is large and represents a world of investment opportunities. As shown in Exhibit 1 below, nearly half of the investment opportunities in global equity markets lie outside the US. Non-US stocks, including developed and emerging markets, account for 48% of world market capitalization and represent thousands of companies in countries all over the world. A portfolio investing solely within the US would not be exposed to the performance of those markets.

Exhibit 1: World Equity Market Capitalization

At Trust Company, we retain a slight home bias. Our neutral US to International equity mix is 65% US and 35% International. This positioning largely stems from a thorough study performed by Vanguard. The analysis looked at the minimum variance (i.e. greatest risk reduction) point between US and international stocks for an investor based in the US. The researchers at Vanguard found that a range between 30% and 40% invested internationally saw the most benefit. This study was updated in February 2019 with similar findings.

THE LOST DECADE

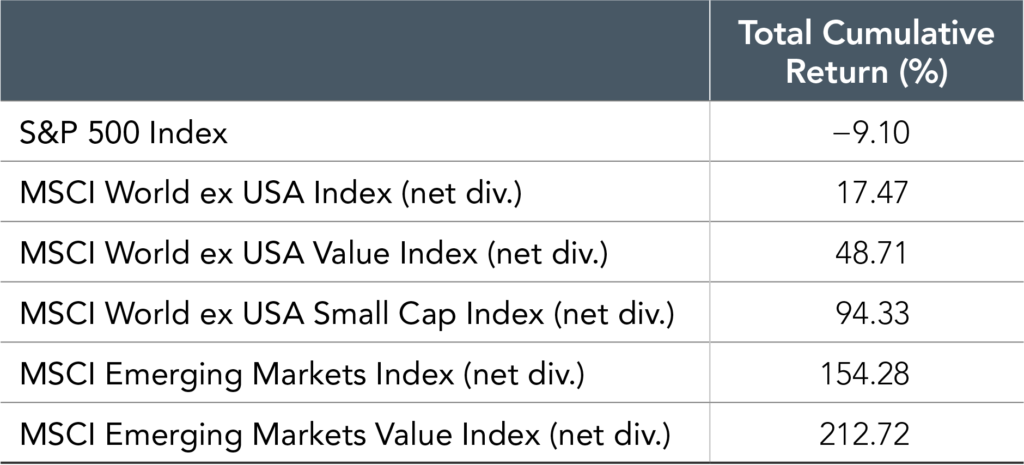

We can examine the potential opportunity cost associated with failing to diversify globally by reflecting on the period in global markets from 2000–2009. During this period, often called the “lost decade” by US investors, the S&P 500 Index recorded its worst ever 10-year performance with a total cumulative return of –9.1%. However, looking beyond US large cap equities, conditions were more favorable for global equity investors as most equity asset classes outside the US generated positive returns over the course of the decade (See Exhibit 2 below). Expanding beyond this period and looking at performance for each of the 11 decades starting in 1900 and ending in 2010, the US market outperformed the world market in five decades and underperformed in the other six. This further reinforces why an investor pursuing the equity premium should consider a global allocation. By holding a globally diversified portfolio, investors are positioned to capture returns wherever they occur.

Exhibit 2: Global Index Returns, January 2000 – December 2009

A DIVERSIFIED APPROACH

Over long periods of time, investors may benefit from consistent exposure in their portfolios to both US and non US equities. While both asset classes offer the potential to earn positive expected returns in the long run, they may perform quite differently over short periods. While the performance of different countries and asset classes will vary over time, there is no reliable evidence that this performance can be predicted in advance. An approach to equity investing that uses the global opportunity set available to investors can provide diversification benefits as well as potentially higher expected returns.

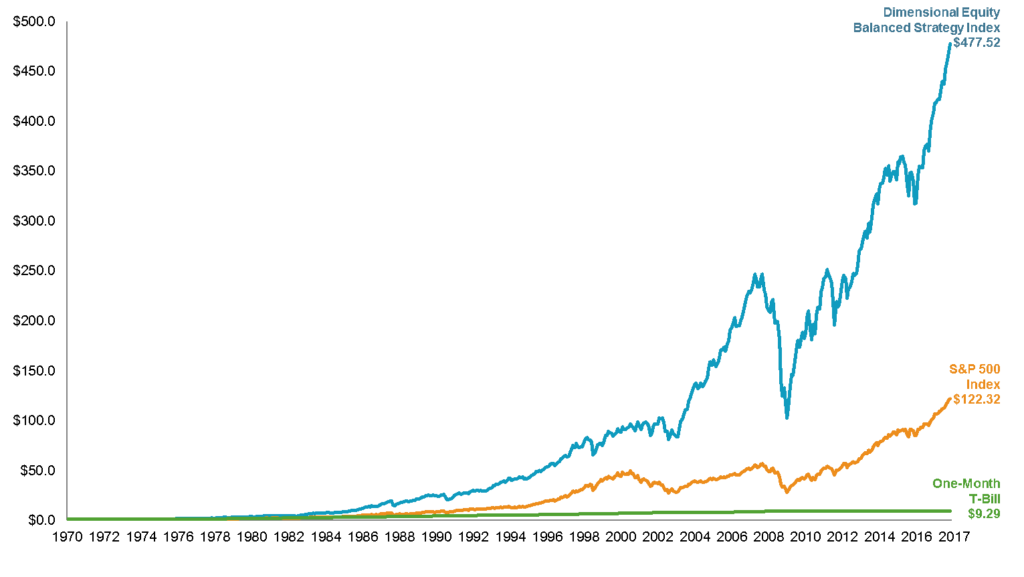

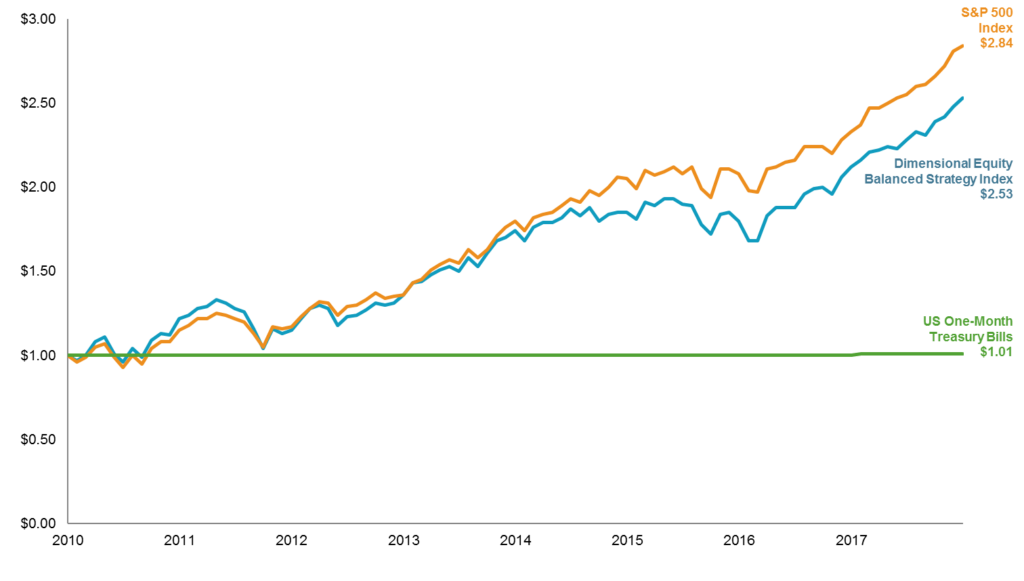

Our partners at Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA) provided a study of a globally balanced portfolio compared to the S&P 500 which goes back to 1970. The globally balanced portfolio is a 70/30 split between US stocks and international stocks with tilts to value and small companies. Exhibits 3 and 4 below compare the long-term success of the globally balanced portfolio (Exhibit 3) relative to the S&P 500 with the recent short-term outperformance of the S&P 500 (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 3: Long-term (January 1970 – December 2017)

Exhibit 4: Short-term (January 2010 – December 2017)

A BIASED MIND

One of the most common investment conversations we have had with clients over the past decade has been our US to International weighting. Even with our underweight position to International equities, many clients have questioned the benefits of having International equity exposure at all. The data found in this piece provide a clear answer. Still, the questions continue and, in fact, are quite natural.

The field of behavior finance has exploded in recent years with many insights into humanity’s inherently flawed brains. The human brain is remarkably complex and able to perform great feats. Little children learn to speak and understand language within months of being born. We have built upon knowledge over centuries to spur new technologies such as the printing press, the automobile, computers, and today’s smart phones. The extents of our brains’ potential is still not fully known. Yet, we regularly call our kids by the wrong name, lose our keys, and struggle to remember what day it is. Maybe this is just this writer’s experience, but all of us can likely point to something quite simple that we simply cannot get right.

In his seminal work Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman describes two systems in our brain: system 1, which governs about 90% of what our body does every day and system 2, which does all our strong computing and analysis. Our system 2 is quite good and is responsible for humanity’s great triumphs. Our system 1 is quite bad, and in many cases, it is worse than animal brains. Our system 1 is quick to form error prone thinking habits without our even realizing it. Outlined below are a handful of common system 1 flaws that have very likely influenced investors in the debate regarding the optimal US to International equity mix.

If you are wondering if you have flawed thinking about your US to International equity mix, then reflect upon the arguments presented in this research piece. If the facts discussed herein leave you unconvinced about the necessity of diversification to international equities, then maybe one of the below biases is at work in your mind.

Recency Bias: Easily remembering something that has happened recently, compared to remembering something that may have occurred a while back.

- Example: Say you live in upstate New York. During the last two winters, this part of the country has received less than a foot of snowfall each year. Despite a long-term average of snowfall of 80 inches per year, you focus on recent winters and decide to forgo the all-wheel drive in your new car purchase.

- Application: The S&P 500 has outperformed recently. Despite data showing global diversification as a superior strategy over a long time period, your brain incorrectly thinks that international equity does not warrant a place in your portfolio.

Familiarity Bias: Preference for familiar or well-known investments despite the seemingly obvious gains from diversification.

- Example: Say you are a banker. Working as a banker for decades, you develop an expertise in what drives success and creates value for banks. Using this expertise, you invest all your assets in bank stocks in an effort to outperform the market. Little did you know, interest rates were about to move in a way that was extremely harmful for banks. This event was unknowable and completely outside of your area of expertise, so this unexpected interest rate movement created massive losses in your portfolio, even if you owned the best bank stocks.

- Application: Investors across the globe show a strong home bias. In 2018, Charles Schwab performed a study on the UK’s home bias. The study revealed that 74% of UK investors hold a majority of their equity exposure in UK stocks. The UK is less than 5% of the global market. On top of that, 71% of UK investors believed that their country would be the top performer in 2019 despite Brexit and numerous unknowns surrounding this impending event. This same phenomenon takes place all over the world, not just in the US and UK. As a starting point, it’s far more likely that any investor is below the optimal allocation to international stocks rather than above it.

Confirmation Bias: Tendency to seek out and interpret any new evidence as confirmation of one’s existing beliefs or theories.

- Example: Consider a Presidential election cycle. A majority of Americans will make up their minds about candidates in advance then reinforce these views through their interpretation of facts. Moreover, many media outlets disseminating these facts are biased themselves.

- Application: Financial media in the US focus almost entirely on the US. This is not surprising. This is where their viewers reside. Financial media outlets are not in the business of financial advice; they are in the business of financial entertainment. Consider 2017, when the S&P 500 was up 22%. International stocks were up 27% with the emerging markets subset up 37%. This divergence in performance made little news and caused even less concern among US investors. Why did this go unnoticed? It was not widely reported, and when it was, the information was automatically minimized in the brain of a US investor. Since this fact does not support a naturally occurring home bias, it is quickly dismissed by the brain.

As the field of behavior finance continues to expand, many lessons will be learned. It is still not entirely clear what happens inside our brains that causes these flaws in our thinking, and it very well may be different for each individual.

To offer an amateur theory, we would point to a desire for control or certainty which are both fueled by fear. Most clients we work with have seized control of their careers, companies, and lives in general to meet goals. Generally, this proactive approach has led to much success. Unfortunately, markets do not work this way. You cannot manufacture returns in the way you can manufacture widgets. You cannot try harder to make the market go up. We have zero control over the market. We can only control our positioning relative to it, since we do control portfolio allocation, portfolio costs, and our reactions to portfolio volatility.

Thus, investing requires a release of control, a view of the long-term, and (of course) a globally diversified portfolio with an optimal mix of US to international stocks.